Are We Heading for a Recession? What Unemployment and the 10-Year Interest Rate Are Telling Us

- Jaden Souza

- Apr 29, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Oct 15, 2025

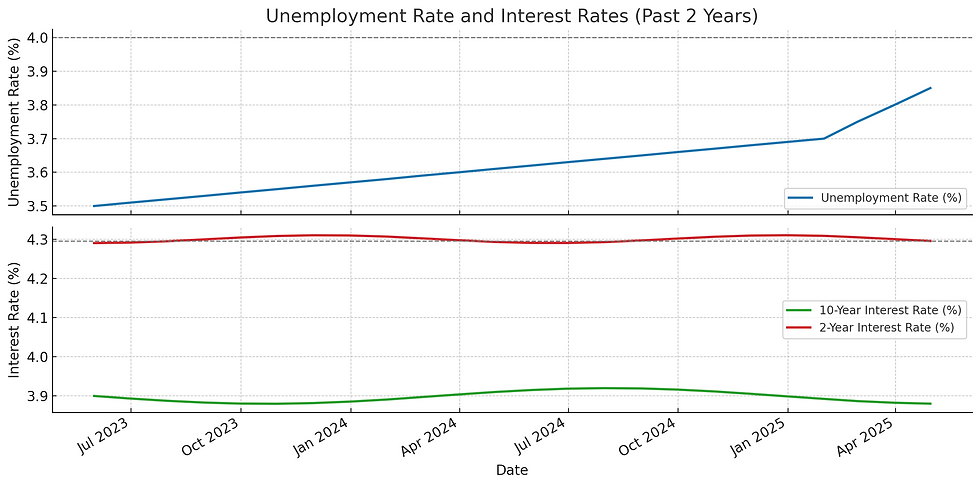

This is the question hanging over every investor, policymaker, and paycheck: is the U.S. economy on the edge of a recession? Despite the Federal Reserve holding interest rates steady and inflation cooling slightly, warning lights are still flashing across financial markets. The job market looks strong at first glance because unemployment remains near historic lows, but the bond market is telling a different story. The 10-year interest rate continues to signal long-term uncertainty, even flashing the infamous inverted yield curve warning for months. These two indicators, the unemployment rate and the 10-year interest rate, have predicted recessions in the past. But what happens when they don’t agree? Let’s break down what the data actually says.

As of March 2025, the U.S. unemployment rate stands at 3.9%, only slightly above the 50-year low of 3.4% set in early 2023. Historically, unemployment is often low right before a recession. Layoffs usually lag because businesses do not cut workers until profits begin to fall. One key rule economists watch is the Sahm Rule, which signals a likely recession when the three-month average unemployment rate rises 0.5 percentage points above its 12-month low. So far, that trigger has not been hit, but the gap is narrowing. If the current soft uptick in jobless claims continues, the Sahm Rule could flash red by summer. The unemployment rate looks calm now, but historically that is often when storms begin to form.

Now let’s turn to the bond market. The 10-year Treasury interest rate, a benchmark for mortgages, corporate debt, and market expectations, has hovered around 3.85%, while the 2-year Treasury has remained near 4.5%. That is an inverted yield curve, where long-term interest rates fall below short-term ones. This inversion has preceded every U.S. recession since the 1960s. When investors expect economic trouble ahead, they buy long-term bonds like the 10-year, which pushes its yield down. Meanwhile, the 2-year rate stays high because of current Fed policy. The result is a market signaling recession even though the unemployment numbers have not caught up yet.

The current inversion has lasted for more than 15 months, making it one of the longest on record. Historically, recessions tend to follow about 12 to 24 months after an inversion begins. If the pattern holds, we may already be in the early stages of a downturn.

Here’s the tricky part: unemployment and interest rates are not telling the same story. One suggests strength, the other fear. That is not unusual and often happens in the late-cycle phase of the economy. The job market stays tight from previous momentum while financial indicators show strain. This same setup appeared in 2006 and 2007 when unemployment hovered around 4.5% while the yield curve inverted. A year later, the Great Recession began. There have been false alarms as well, such as the brief inversion in 2019 before the pandemic.

This mismatch of signals leaves the Fed in a difficult position. Cutting rates too soon could reignite inflation, but waiting too long could tip the economy into a sharper downturn. The bond market is pricing in that uncertainty.

For now, the surface looks smooth. Unemployment is low, consumers are spending, and GDP is still growing. But the 10-year interest rate and the broader bond market are whispering a different story. Inverted curves, cautious lending, and long-term rate suppression all point toward a slowdown. Whether that slowdown turns into a full recession depends on how quickly the labor market cools and how the Fed responds. If history is any guide, when unemployment and the 10-year rate start to drift apart, the gap often closes with a downturn.

The data may seem quiet, but it is beginning to shift.

Comments